Updated 13 July 2020 – Mid COVID-19

In the Spring of 2020 teachers and students around the world were thrust into the environment of online learning. Few teachers and students (and parents!) had any experience with teaching and learning online and this new experience came with the added stress of social distancing, quarantines, family sickness, and even the loss of loved ones. One major dilemma faced by teachers, schools, and districts was what to do with grading. While the answer for many was to adopt a pass/fail system, this option was met with even more uncertainty from teachers who worried if students would do much work at all when points and grades were missing as an incentive. However, the switch to the pass/fail approach in online teaching and learning was almost seamless for some teachers and their students. These teachers and students were already living in a pointless world, that is, their classes were being taught without points and, for some, even without grades.

One of these teachers is Language Arts Teacher, Sarah M. Zerwin. In March, Dr. Zerwin published a book on the pointless classroom: Point-less: An English Teacher’s Guide to More Meaningful Grading. In an accompanying blog post for the publisher Heinemann Zerwin argues that with a pointless and even gradeless (Pass/Fail) system, “you are free to imagine the most engaging tasks you can for your students without having to think about how you’ll grade them. It will take a bit of a leap of faith to trust that students will want to do the work. But they do. Really.”

While Zerwin writes from the perspective of a teacher of reading and writing, the pointless approach is universal and has been at the center of my biology classes since 2015; I am also pointless in my science research and anatomy and physiology courses.

(Full disclosure: Sarah Zerwin and I teach at the same high school, we are married, and she is the sole reason I moved to my pointless system in science.)

What I do

The stop grading movement is an evidence-based attempt to reduce student stress as well as put the student’s focus on confidence, skills, and learning and understanding of concepts and away from merely accumulating as many points as possible in a course as a means toward a grade. Ideally then, students begin to focus on what really matters in their education and growth instead of a running point total and a constantly and automatically calculated and updated grade.

Unfortunately, most of us are stuck in various ways with a grade book system that requires some kind of quantification of learning. Even so, I argue here (and Sarah Zerwin does in far more detail in her book) that there are ways we can fulfill the grade book requirements while filling the grade book with meaningful data that really matter to students, teachers, and in K-12 education, parents.

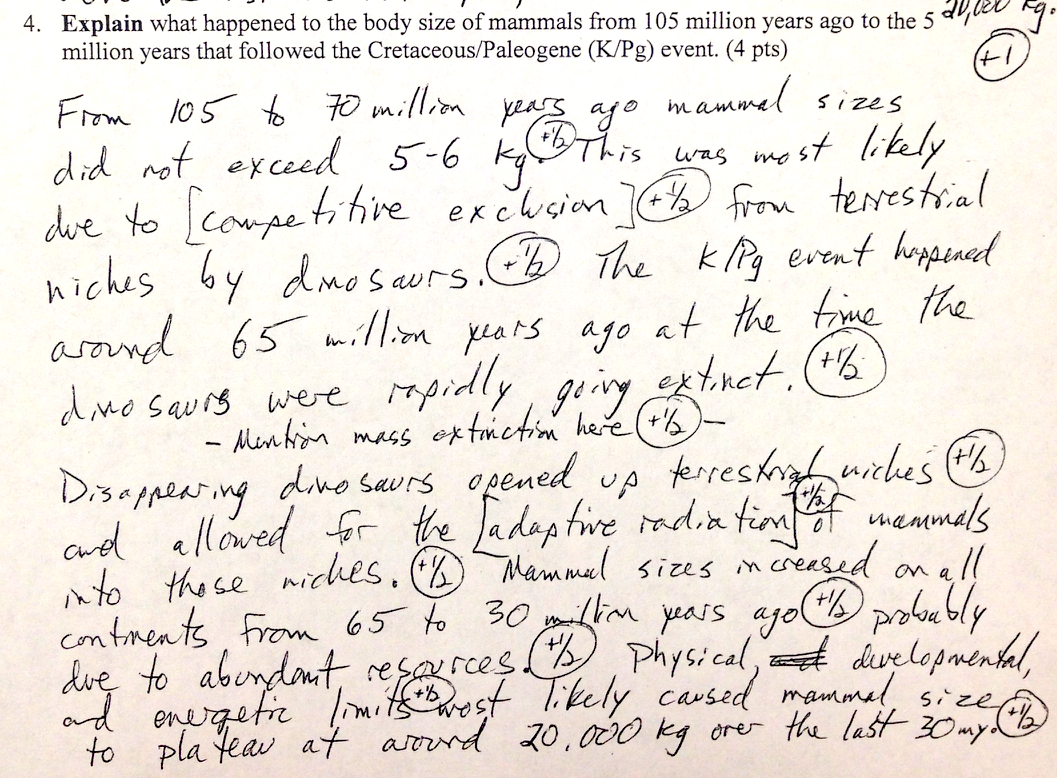

I do not put a single point or grade on an exam, paper, worksheet, quiz, you name it. Indeed, for years I had become more and more uncomfortable trying to assign arbitrary point values for student work, combined with figuring out how and where students could earn points and partial points on their work. The image below (and this student email) shows how crazy things had gotten. I wanted to eliminate unnecessary complexity that comes with point-giving and the power struggle that comes with points-as-currency. Indeed, we have all had students ask questions like, “Why didn’t I get any points for this?” and “Can I at least get half credit?” and “Can I get some points back if I turn this in again?“ (as if they had points to begin with and I took them away) and “Is there any extra credit I can do that’s worth points?”

In my biology classes, students do end up with a grade at the end of the semester, they have to. Indeed, my school and District require it. However, how we get to that final semester grade does not have to include points.

The approach I take has several components

Journal. Students in my two content courses keep a digital journal. The journal is a Google Document that is shared with me and on which I can make comments. In the journal students reflect on what they have enjoyed learning and doing in class and what they haven’t, what they have found difficult as well as easy, what mistakes they have made and how they corrected them. Students also post photos of the work they are proud of, from images of their lab notebook pages to pictures of themselves with a freshly built glucose molecule, to a diagram on a unit exam they thought was well done. Students even pose questions to me and provide feedback on the activities we do in class.

This isn’t a new idea—it is similar to the Interactive Student Notebook my colleague Lee Ferguson uses and a student Learning Record.

Exam and Writing Revisions. Students take their Unit Assessments twice and the assessments are entirely free response. The first attempt is a solo effort. I read through the papers, check-mark the answers I think are done well and circle the ones that need more work. I provide some feedback, mostly in the form of questions about their answers. I then give each student a level of progress on their solo efforts: Complete (100%), Partial (75%) or Rework (50%) (see Assignment Mark Detail below).

Students understand that achieving a Complete does not mean perfect, it simply means that the student has shown a remarkable degree of progress toward the Unit goals. I enter the progress level for the solo effort in our online grade book and include comments for both students and parents to see about some of the major items on which the students need to focus (see Unit 3 Exam Solo below). Students then revise their assessments by themselves or with classmates—including students at the Complete level—and turn their papers back in for me to have another look. I provide time in class for these revision sessions and I take the opportunity to move around and confer with individuals or groups of students.

Note: Students and Parents are guided to interpret “points” in the grade book as progress.

Mentor Texts, not Rubrics. Student writing assignments are also assessed progressively using the same levels of completion as exams. I provide students with mentor texts to help them with their scientific writing. The mentor texts include good examples of previous student writing and actual scientific papers from which students model their own writing.

But I don’t use writing rubrics, I just provide constant feedback. For example, with a rubric, if a student receives a 4/4 for their introduction because all the components are there, but they still could improve their research question or hypothesis, what motivation does the student have to improve? In my courses, if a student receives a Partial (75%) I think of this as akin to what an author trying to publish in a peer-reviewed scientific journal would receive: Accept with Minor Revisions. Indeed, from this perspective, all of the journal articles I have published began at essentially the Rework (50%) level: Accept with Major Revisions. The drafts of each manuscript were covered with feedback; no scores, just lots and lots of challenging but helpful and encouraging feedback.

So, shouldn’t we be authentic to our subjects and one of its major crafts (e.g. science and scientific writing) and model this feedback approach for our students? My guess is that most teachers do provide valuable written feedback on student writing. While it’s difficult to divorce ourselves from scoring student writing with rubrics and points, it’s not impossible and the change can be freeing for both student and teacher.

A Grade Book Comparison

Below are grade book snapshots of three courses taken by a student. Notice that points are the only data available to students and parents when they view the online grade book for economics and calculus. In my courses students and parents are constantly reminded that students do not have grades until they select them at the end of each semester. Instead, they have itemized and overall levels of progress.

In traditional courses student remained focused on growing their piles of points.

The End of Semester Grade Selection

So how do my students end up with the fair and accurate grade I am required to give? Students write a letter to me at the end of each Semester where they pull the best of the best evidence from their journals, make a grade level selection, and back their selection up with logic and reason. For example, below is the grade guide that I provide to my Anatomy and Physiology students (and their parents) at the beginning of the year.

The Pointless Anat and Phys Classroom and Getting to the Semester Grade

My method for getting to a Semester Grade is different from many teachers. My inspiration comes in large part from The Case Against Grades by education researcher, Alfie Kohn. While we are required to land on a grade at the end of the semester, how we get there can look different. In my Anatomy and Physiology course, students will not receive points on any work. Instead, all turned in work will be given feedback, a level of completion/progress, and entered in Infinite Campus as follows:

- Complete (100%) – work is really well done with great effort, yet it still may have areas that need improvement. The expectation is that students do the improvement work and show continued progress toward learning, understanding, and skill development.

- Partial (75%) – effort and understanding is mostly evident, but there is still room for a good amount of growth toward learning, understanding, and skill development.

- Rework (50%) – work is far from the level of expectation in the class and requires a major overhaul to reach the desired level of learning, understanding, and skill development.

- Missing (0%) – work is missing.

The Concept of Progress

The “grade” and percentage you will see in the Infinite Campus Gradebook throughout the semester is not your grade. The grade and percentage is your PROGRESS toward an ultimate level of achievement (the grade) at the end of each semester. Indeed, it is possible that Infinite Campus shows that a student is ultimately progressing at 90-100% throughout the semester but the student has been late with several items, has never communicated with me about them, is a distraction for other students in class, is not keeping up with the Anatomy and Physiology Journal (see below) etc. Thus, the student does not fully fit the profile of an A student.

Seventy percent (70%) of your semester progress will come from the Unit Exams, the Semester Final Exam, and the Lab Practicals. Thirty percent (30%) of your progress will come from everything else that is turned in for feedback. Much of the daily work you will do in the class will not be formally turned in, but this work you do is important practical and practice work that will help you with understanding the basics of Anatomy and Physiology.

The Anatomy and Physiology Journal

Students who have realized the greatest success in my Biology courses over the last five years have kept a consistently updated Journal. The Anatomy and Physiology Journal is a Google Doc that you will submit through Google Classroom twice a semester. You will have ten minutes of class time on most Fridays to update your journal with written reflections on how each week went: what was interesting, what was difficult, what challenges were overcome. Successful students spend an additional 15 minutes per week updating their Journals. Successful students also illustrate their Journal pages with images of their work and activities; images of fun and meaningful moments in class, images of their best work, including work in their Notebooks. The Anatomy and Physiology Journal then becomes the primary source of evidence of progress and success when you present your thoughts on what grade you have selected each semester. Ultimately, you are the most important user of assessment data and the Journal should reflect this.

The “A” Student Profile

Below is a profile of an A student. Think of this profile as a list of the goals for having a Fabulous and Excellent Semester. If students put effort into 1-8, then 9 and 10 should come naturally.

- Evidence that you have attended class on every single day possible with no unexcused absences.

- Evidence of no Missing work.

- Evidence of no Late Work unless you received permission for late work from Dr. Strode before the work was due.

- Evidence of meetings with Dr. Strode during Collaboration and Access Time (CAT) or office hours to discuss each assignment that is assessed in at the Rework level in IC.

- Evidence that your work is yours, is authentic, and is completed with integrity, and care in all areas of the course–this includes on solo efforts on assessments, the revising of your assessments, scientific writing, and the Anatomy and Physiology Journal (which includes lab work).

- Evidence of reaching a Complete in IC on all items (except for solo Exam efforts, these remain at your first attempt levels).

- Evidence that you have been a positive community member: You have provided helpful contributions and feedback on exams and group writing, engaged in effective conversation in class, helped others, navigated our classroom with kindness, and did not distract others or limit their success.

- Evidence that you have completed meaningful and consistently updated work, not “just get it done” work, in your Anatomy and Physiology Journal.

- Evidence that your work is your best work possible and your effort is consistent toward the purpose of learning and understanding this semester’s biological concepts and science practices. The Anatomy and Physiology Journal is a great place to illustrate this profile component.

- Evidence of improvement on content understanding throughout the semester, including a consistent effort on any Semester Final Exam or Culminating Experience.

The Grade Selection Letter

At the end of each Semester each student will write a letter to me that highlights the student’s reasoning for how the grade was selected based on the description above. Successful students that have kept a Journal of their work throughout the semester simply add their letters to the top of the Journal at the end of the semester and submit it to Dr. Strode.

Below are the grade levels students can select for the semester. Please do not think of the grade as something you deserve, but as an accomplishment you certainly have earned.

A = You are confident that you exemplify the full profile outlined above. If one of the descriptions does not fit you, clearly explain why the A still is an accurate achievement for you.

B = You are confident that you exemplify most of the descriptions, but you CLEARLY and honestly have some room for growth in more than one area.

C = You honestly only fit some of the descriptions outlined above, leaving clear room for growth in several areas.

D = You fit less than half of the descriptions outlined above.

F = None or only a couple of the descriptions above describe you as a student in Anatomy.

Example Student Grade Selection Letter (COVID-19 year)

Student Feedback

I survey my students at the end of the year. I ask students various questions about the course. In the next two figures below I have provided summaries of their answers to the questions I asked that were most relevant to the pointless and grade de-emphasis approach. One result I found hopeful was an overall sense of low stress, control, and a focus on learning and understanding.

An interesting difference in the free response answers was that some of the seniors thought that my approach to grades took the focus too much off of their end-of-year IB and AP Biology Exams. As a result, some students felt under prepared for these external assessments. However, and at the risk of contradicting the entire argument of this post, many readers might be interested to learn that overall scores on the IB and AP exams by the seniors in my courses have actually increased over the years both before and after implementing my approach to grades, and even given new requirements in both curricula that began in 2015.

- The seniors were understandably somewhat focused on the IB and AP Biology Exams in May of a non COVID-19 year. These students took the survey after these culminating exams.

Where to now?

I am pretty sure that my courses and approach to learning and understanding, the science practices, and grades will continue to evolve over the remaining years of my career. But one thing is for sure: I will do my best to take risks, to be innovative, to listen to my students and to my colleagues, and to keep the focus on improving science literacy, critical thinking, and fostering an overall love for the biological sciences in my students.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic of 2020 has forced all educators to rethink teaching and learning. Perhaps we can use this experience to finally help us move away from using points and grades as student motivators and toward helping students focus on what truly matters: the learning.

Dr. Strode,

A colleague and I are considering shifting to a point-less (seems pointless to call it grade-less since there is a grade) in Chemistry/AP Chemistry and Biology/AP Biology. I am trying to gather as many resources as possible to help make my, and maybe our, transition to a point-less classroom as smooth as possible for everyone involved. We also use IC so I’m most grateful for your pictures explaining what you did.

I was wondering if you still use the summative/non-summative grade method that is described in “What I Learned from a Year of Going Gradeless” or if the only thing you use now is the form described in this post and linked in your Google Drive? Not sure what I feel about the more “scientific/mathematical” way described in the other post verses the more open-ended/subjective method described in the Google Doc.

Also, did you switch from the 70/30 or 80/20 breakdown of major and minor assignments during the semester to the final grade being 100% and those being 0% to keeping the 70/30 or 80/20 breakdown through to the end?

Any help/advice on here or via email would be most appreciated. My principal is 100% behind this and anything that would help me do a decent job would be awesome!

-David

LikeLike

Hi David: Thanks for you comments! Follow this link to my latest letter to parents describing my approach: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1q9jNP2n1K82h2V3XAna6KKWckfvCx_x1X90WIS_s6ZQ/edit?usp=sharing

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this. I started using this system last year. I think it worked wonderfully, and I have some pretty stark data to support it! (Oh, and I’m a msdrscienceteacher … ) Take care!

LikeLike

I love it! Best to you!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Mr. Dr. Science Teacher and commented:

In the last week there has been an increase in the interest of this blog post from three years ago. I have updated it to include where I am now with this teaching and learning approach.

LikeLike

What a great post- Thanks for sharing and updating! I would love to see an example of a Biology journal if you’d be willing to share. I teach music and started with gradeless last year but didn’t feel like the journal I used was particularly effective.

LikeLike

Do you think this would work for basic biology students? I have a lot that are lower level that are extrinsically motivated by grades.

LikeLike

Hi Rebekah: Yes, it will work for basic biology students. I teach Anatomy and Physiology as a pointless course and most of my current students came through our College Prep (regular/basic) science courses. I think it’s a relief for them that they don’t have to be measured by points and can just come to class and enjoy the work. The grade then comes naturally.

LikeLike

Have you changed how you teach? Are there still lecture and multiple choice tests? The way I’m imagining it, tests would have to be completely short answer to allow for me to really see what’s going on in their minds and if they really understand. I don’t mind the grading, I’m having a hard time coming up with tests.

For daily work, do you just do completion grades if they’ve done the work? How closely do you look at that type of assignment?

I have a few students that pulled off a D- minutes each quarter by completing minimal work. What makes you decide between a D- and an F? What do you do when you don’t agree with grade they write a letter for?

LikeLike

I still deliver material with slides and students seem to enjoy those discussions. Most of my slides are images of graphs and other phenomena and, in normal times, students discuss the implications of the graphs at their table groups and share out to the whole class.

I no longer use MC or T/F questions on my summative assessments. My Unit Exams are all free response. However, I do provide MC and T/F questions for students to check understanding and discuss with their table/working groups.

In normal times, students bring any daily work to class and I start class by having them discuss their answers with their table groups and then we talk as a class. I do not collect this kind of work. Instead, this work goes into their Journals as evidence of their engagement. During table group talk, I move around the room and join in on conversations and make note of who came prepared and who did not. I can later check in with those students who are not keeping up to see what their obstacles are and give them encouragement. Thus, I don’t penalize them for not doing the work, but they end up without much to show at the end of the grading periods.

The guidelines are clear for how students select their semester letter grade. I remind them that we are both looking at the same data and the same guidelines. If I disagree with a student’s grade selection (1-3 each class), I ask them to have a conversation with me about their selection process that goes beyond the letter they write. When students have to justify their selection in person, it quickly becomes clear to them that they are misrepresenting the work they actually accomplished.

Great qeustions!

LikeLike

Thank you for this post! I am currently working through my pre-service teaching in my graduate program, and I found this information to be extremely helpful! I recently had a guest speaker in one of my classes discuss the effectiveness of grades and the kind of negative effect low grades in a gradebook can have on students’ mental health. While I love the idea of not using grades to track student progress (because I also believe they are relatively arbitrary), I had no idea of how to implement this idea in my future classroom. Your post has really helped me gather information for what a “pointless” class would look like! I love the electronic science journals the students keep. Hand-writing a science journal when I was in high school was one of my least favorite things to do. I was a very slow writer, and I always found it tedious. The idea of keeping a Google Doc to make comments on throughout the course of the semester is brilliant! The students can easily go check it without having to physically turn over their journal to you, and I think that is so helpful. They also can’t lose it, which I love. The way you grade exams is also great to me. I wonder if you have found that your students are not as discouraged by getting something wrong or knowing they need to improve more to get closer to that “Complete” mark as opposed to just getting questions wrong? Something else I truly love about this setup is the feedback for writing. The idea of mentor texts is amazing and something I hadn’t thought of before. Students can write in such different ways, so providing a rubric seems so rigid to me. The entire time I was reading this blog post, all I could think about was the fact that this seems to encourage students to take risks without fear of being penalized, and I saw that you mention that about half-way through your post. The student feedback really says it all. They seem to really appreciate your approach to teaching them and wanting them to actually learn the material instead of just aiming for a high grade. I can only imagine how much better I would have felt in school if my teachers had implemented a similar grading system. I truly appreciate you sharing your work on this. I hope to implement a similar system in my future classroom!

LikeLike